The small change that would make Strava safer for women

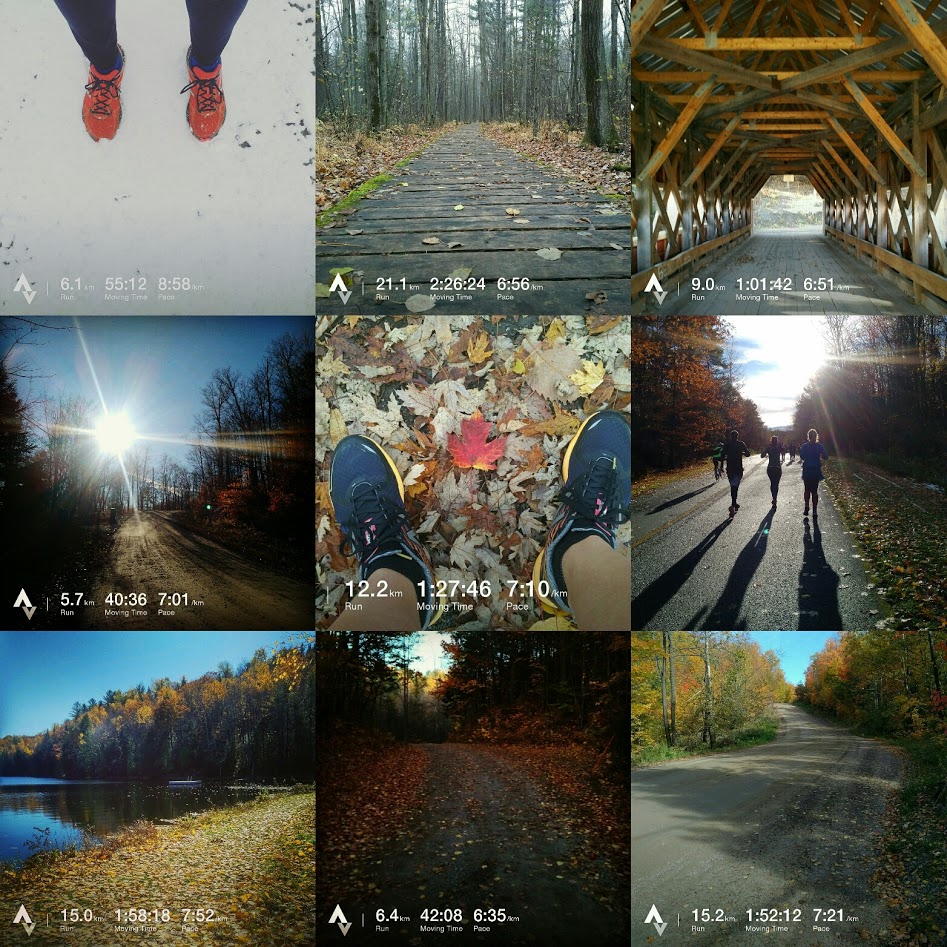

/If you follow me on instagram, you probably know that I'm a runner. I like to run in the woods, to discover new trails, to sign up for challenging races.

I've also been a social media fanatic for much longer than I've been a runner. When I discovered the community that exists on Strava, I was quick to start using that to track my runs instead of the app I'd been using previously. I followed people I was already friends with, I joined some groups, I followed some local runners.

I love being inspired by other runners on Strava. I love being able to discover new routes. I love knowing that when I'm out there struggling on a bad day, that my friends are out there too. I love being part of groups and taking part in challenges.

Private runner

But I'm only half there. If you follow me on Strava, you're only seeing about half of my runs. My other runs don't show up in your feed. When you look at the stats in my profile, it will tell you that I ran 117km and climbed 1,276m in October. When I look at my profile, it tells me that I ran 151km and climbed 2,211m in October. Many months the difference between what I actually ran and what my public profile says that I ran is the difference between getting a challenge trophy and not getting a challenge trophy.

The reason those other runs don't show up is that they are private. When I run out my front door and around my neighbourhood, I mark them as private. When I mark them as private, you don't know anything about that run. You don't know where I ran, you don't know how far I ran, you don't know fast I ran or how high I climbed. I could have been at home sitting on my couch, but I was out there running.

I think it is great that Strava lets people mark some workouts as private. We don't always want people to know when we're working out. But I think there are probably lots of times when people, especially women, don't mind telling people that they were running but they just don't want to tell people where they are running.

I go out. I do the work. I track it. Yet Strava doesn't give me credit for it or let me get kudos for it.

But what about privacy zones?

Yes, Strava lets people mark a privacy zone around their house or their place of work. That means that when it shows a map of your run, the starting point and ending point won't show if they are within your privacy zone. There are a few problems with this:

- The maximum privacy zone is 1km. So if you live in an area that is sparsely populated, it is still pretty easy for someone looking at your maps to narrow down exactly where you live.

- If you do a run that is entirely within your privacy zone, it still shows a map, there is just no trace of where you ran. So that map is, again, pretty much a bull's eye of exactly where you live.

- If you follow a specific routine (e.g. a 5k run after work each Monday), people will still be able to see exactly where you exit and re-enter your privacy zone.

An easy solution - "Hide map"

There is a really easy solution to this problem that would make Strava feel a lot safer for women or other people who want to be a bit more private about where they run, but that still want to participate in the community aspects of Strava, like sharing their runs, participating in challenges, and so on.

Just give people an option to "hide map" on individual workouts.

Strava has the GPS data. Strava can show the map to the user. Strava can verify through the GPS data the fact that the person did run that distance and therefore can be eligible for those challenges. But Strava runners (and cyclists and walkers) can maintain a greater degree of safety by not sharing the geographic location of their routine runs or where they live.

If I could hide the map, I'd still show the map for my one-off runs in interesting places. I'd show the maps for my races. I'd show the maps for groups runs or other situations that feel safer. But I'd hide the map for runs that start at my front door or that are part of a regular routine. I'd still like to show my distance, my speed, my elevation climbed, and even heart rate data, splits, and even some pictures.

Just not the map. Just let us hide the map.